Who the f*ck did I think I was?

I was just a 20-something nobody. These were important men who did important work. Why in the world would they hire me as a consultant?

Perched high above the humming Manhattan streets, I was nervously quivering inside the most wildly intimidating board room I had ever seen.

I couldn’t focus. The iconic Brooklyn Bridge loomed just outside the window. It taunted me with its tenacity and importance.

Oh god. 🤦

🍻 THE DRUNK BUSINESS ADVICE

👉 Stop selling. Start solving.

👉 The gap between what they assume, and what you know to be true, is where all your leverage lies.

👉 The trick isn’t learning to talk better. It’s not even learning to listen better. It’s learning to see better.

And now — the story behind why this advice matters. 👇

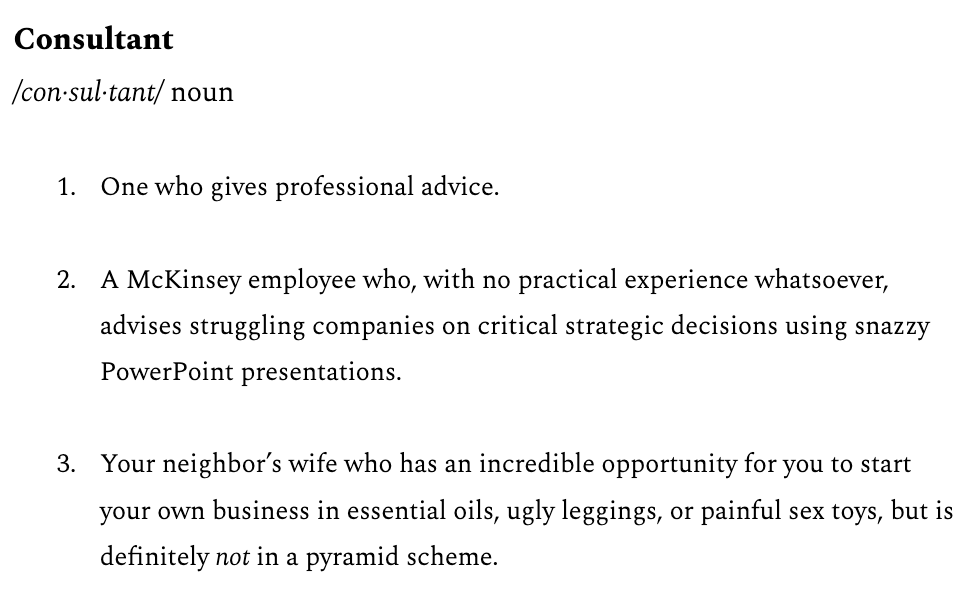

What is a consultant?

I’ve thought long and hard about this question, and eventually settled on the following three definitions:

If you happen to be a consultant, and you’re reading this newsletter, I dearly hope you fall under the first definition — otherwise we’re going to need to have a little chat.

That first definition also applied to me for a period of my career. In my case, I realized that I had unique expertise that could benefit a lot of blue chip real estate companies. But I had an employability problem — most of those companies didn’t require my expertise on a permanent basis.

And let’s face it. I’m a shitty employee. 🤦

So I was stuck taking jobs that leveraged a little bit of my “special sauce”, but mainly filled my plate with stuff that I could competently do, but wasn’t thrilled about. I got bored quickly. I got annoyed by the red tape and politics. And I would give my left tit to never get called into HR again.

Finally, in my late 20s, having spent most of my young career launching new subsidiaries for established firms, and co-founding a successful startup of my own, I decided it was time to zero-in on my expertise, and establish a consulting practice as my full-time focus.

I figured that since I was already an “experienced entrepreneur”, running a consulting business would be a breeze.

Um. No.

Just because you’re an in-demand-subject-matter-expert, or even an experienced businessperson, does not mean you’re qualified to run a consulting practice. Pretty much nobody is when they start. And nobody actually realizes how unqualified they are when they start, either.

Operating a consulting business is a skill that no one possesses until they do it for a while. Every time I talk to someone who is new at consulting, the same questions arise:

“How much should I charge?”

“How do I screen clients?”

“How do I fire clients?”

“What should I do when a client doesn’t take my advice?”

“How much of my expertise should I “give away for free” to sign clients?”

Those are all important questions, but none of them matter until you’ve established the critical gap between what your client assumes, and what you know.

It’s much faster and easier to flip an assumption than to educate from scratch.

And guess what? This nifty little trick applies far beyond consulting. So listen up.

Back to the boardroom…

…Where I was anxiously prattling to three men in dark suits — two of whom were definitely old enough to be my father. These guys were incomprehensibly busy, and I was stunned that they all agreed to meet with me that day.

So, in the blessed short time I had with them, it was my mission to:

Convince them they had a problem

Demonstrate why I was the only one who could solve it for them

This was my first major pitch. I had launched my consulting practice only a few months prior, and none of the client conversations I had conducted thus far came close to the size and significance of the project this team was working on—

The redevelopment of New York City’s Seaport District following the devastation of Hurricane Sandy.

The guys on the other side of the table were legendary pros. George Giaquinto was the VP of Development for The Howard Hughes Corporation (yes, that Howard Hughes) – the lionshare holder of real estate in the Seaport District.

Bill Flemm ran operations for The Howard Hughes Corporation, connecting the dots across all the various initiatives.

And Frank Supovitz, like me, was a consultant — but with a profoundly beefier resume. Having directed the Super Bowl for a decade, he was now lending his entertainment production knowledge to projects like this one.

I had no clue what I was doing in that room with such giants. 🤷

They walked in, shook my hand, and George immediately scoffed, “So how much is this going to cost me?”.

*Cue Kristin shitting her pants.* Source: Giphy

George tightly gripped the purse strings for the redevelopment project — as well he should. He was accountable for every penny that was spent, and the leaders of each initiative kept asking for more and more pennies.

So from his point of view, these guys better have a damn good reason for wanting to throw money at yet another “consultant”.

I knew in my gut that I could add enormous value to this project, but my own fluttering nervousness made the room unbearably tense. I was stumbling — sputtering like a beat-up Vespa, sliding down a cobblestone street in the rain. I spat out some words that seemed correct, but had no clear direction. "The operational efficiency of your development will depend on..."

What an unfortunate moment to learn that I’m ego-crushingly terrible at pitching myself.

Shit.

A few minutes into my self-imposed corporate crucifixion, with the conversation going nowhere, the big boys took pity and decided to roll out some blueprints — literally. And when those drawings graced our table, a portal in my mind swung open.

It was goddamn Amazing Grace. I once was lost, but now am found — was blind, but now I see. I said a little prayer thanking the gods of real estate, because I had truly been saved.

With the plans rolled out in front of me, I could immediately visualize how people would move through the spaces they were building. I knew exactly how the elements of the operation would play out in practice, and could anticipate where things were bound to go wrong. I saw dozens of assumptions I could easily flip.

Finally. I could stop selling. I sucked at selling. I still suck at selling. Instead, I was nose-to-nose with a plan that was rife with problems — and I had solutions to those problems.

So I started solving.

I stood up, and leaned over the drawings. I pointed to design elements, asked questions about their placement, highlighted the issues, and proposed solutions.

This was my kill zone.

I had been so small and meek sitting in that chair — desperate, intimidated, and terrible at “pitching”. Now I was taking up space, controlling the conversation, and showing these guys the value I brought to the table.

I will never forget (nor could I ever repay) what Frank did after about 20 minutes of this. He stood up and said, “Guys, this is the stuff Kristin gets paid to talk about. I think we’ve heard enough to decide if we want to work with her.”

A few days later, they hired me.

The gap you should neatly nestle into

It was pure, dumb luck that this particular meeting went the way it did. And I’m grateful every damn day. Not only because these guys ended up becoming my most valued and enjoyable client relationship — but because, in the short meeting I barely deserved, I got a knuckle-busting crash course on how to run a consulting business.

It’s a simple formula:

Identify the assumptions your prospective client has.

Flip one.

Shut up. (Hat tip to Frank). They can pay for the rest.

Moving forward, whenever I was prospecting a new client, I did my best to procure some sort of visual representation of what they were proposing — because I understood what an important mental unlock it was for me.

Sometimes this involved walking a physical site. Sometimes they had blueprints. And in the absence of those two things, I asked for detailed descriptions that I would personally map out on paper to give myself context before the meeting. Hell, even a napkin sketch would get me halfway there.

Once I had some sort of visualization, their incorrect assumptions became stupidly apparent to me — but not to them. And the gap between what they assumed, and what I knew to be true, was where I thrived.

Frankly, it’s where we all thrive, no matter our profession. But we have a tendency to make asses of ourselves long before that gap actually presents itself.

Why?

Because we’re all trying to look insightful and important. We interrupt. We posture. We try to solve problems we barely understand because silence feels like surrender, and nobody wants to be the one caught without a brilliant comment when the spotlight swings their way.

So we speak first. Or loudest. Or most. Because in this pungent, performative bullshit stew of perception-over-progress, waiting feels risky. We’re wired to chase the mic like it’s a goddamn oxygen tank.

In that fateful meeting, I walked in with a vague understanding of their problem, slid right into my pitch, and completely shat myself in the process. I thought “This is my time to talk, I better not waste it.”

But the trick isn’t learning to talk better. It’s not even learning to listen better (most clients have no damn clue what their problems are anyway).

It’s learning to see better.

The fastest way I found to do that was by literally laying the problem out on paper. When I could visualize it, I could spot the assumptions. I wasn’t guessing anymore, or trying to “sell” them on my expertise. Instead, I was diagnosing problems. And people would listen, not because I demanded the floor, but because I had real solutions.

The smartest people in the room don’t have it all figured out — they’re simply experts in quickly identifying the gap between what other people assume, and what they actually know.

That gap is where all the leverage lives. ✌

Cheers! 🍻

-Kristin